Hot Spots: Columbus Park

From a Lenape village, to the African Burial Ground. From Paradise Park, to Murderer's Alley and The Tombs. From Mulberry Lane, to Chinatown and a 40-story jail.

|

| Columbus Park in Chinatown, 1975 [Nick DeWolf] |

Columbus went in search of China and India, did not in fact find China or India but arrived in the Western hemisphere and called the indigenous people here, what? Indians.

Columbus Park. An excruciatingly ironic name indeed, since this was a place where Native Americans lived, this place now called Columbus Park, in Chinatown. Let's go well beyond Columbus, and Hudson, and back about 400 years.

It's 1619, and the family group (within the Lenape nation) who live on the island are called the Manhattas. 3,000 people live in longhouses right around here. This park is a pond, fringed with thatch houses, corn fields, people at work husking and smoking oysters and fish. The Dutch arrive in 1609 and come to call the pond the Collect (a British transliteration from the Dutch Kalck Hoek, or "Chalk Hook") after the chalky oyster shells piled around the rim of the pond. These shells, sometimes thigh-high, are evidence of thousands of years of Lenape presence. The area around the pond must have been a peaceful place for all to fish and farm and walk around, because there is evidence that the Dutch came here to recreate as early as the 1630s.

But several decades after the Dutch take the tip of Manhattan, they wall themselves off from the Lenape, at the site of today's Wall Street, which means that to come up here, the Europeans have to cross through their own self-imposed border. But after the Dutch Governor tries to "tax" the Lenape against their will, and then sends colonists to massacre 120 people in order to force compliance, a state of war is established in 1643. According to one version ("the Official Story"), the war begins with a series of retributive killings. According to another, the Lenape send a warning by skillfully setting all of New Amsterdam ablaze without killing a soul, and when the Dutch West India Company doesn't get the message, 1,200 Algonquin invade. Most Dutch West India Company workers who had previously engaged in trapping and agriculture beyond the wall retreat into an increasingly crowded and polluted Fort Amsterdam. Barred from their farmlands and the principal sources of freshwater, the Dutch colony grows hungry and demoralized.

|

| Re-imagining of the 1664 Castello Plan of New Amsterdam. [New York Historical Society] |

Here beyond the Wall, their neighbors will be the Lenape living in the village of Werpoes, but these African landowners are expected to act as a buffer and fight the Lenape in defense of the Dutch West India Company; in this regard they resemble their enslaved peers. In the 1660s, Peter Stuyvesant requests more slaves for the purpose of fighting Lenape:

“They ought to be stout and strong fellows fit for immediate employment on this fortress [Fort Amsterdam] and other works; also, if required, in war against the wild barbarians, either to pursue them when retreating, or else to carry some of the soldiers’ baggage."We can understand that rather than fighting the Lenape, many of the enslaved would instead choose to take refuge among them, and fight their kidnappers in the frontier beyond the wall.

The British take over in the 1660s, and as evidences by the above 1667 land grant to an African-American woman named Christina, signed by General Richard Nicolls, the first British governor of New York, the British initially continue the practice of manumission paired with land grants. Ultimately approximately 30 land grants comprising 300 acres are owned by Africans. Thus the frontier beyond the wall comes to be known as The Land of the Blacks. Even after the black population finds their land deeds and the right to own land stripped following the first African revolt in 1712, the historic black presence in this area continues. Since their dead are not permitted inside the colony, the Africans bury their loved ones between here and the colony to the South. The frontier just beyond the fortress wall becomes the African Burial Ground.

(This is only discovered in 1991, when a municipal office building at 290 Broadway is about to go up. Thanks to the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 -- for which Native Americans fight long and hard -- an archaeological dig is required first. 290 Broadway is the backside of 26 Federal Plaza, which houses the Department of Homeland Security and the FBI. It also houses the USCIS - United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, and its 12th floor is full of courtrooms where deportation proceedings take place every day, all day long, in the area of what was once the village of Werpoes. Which brings us to the question, "Who is an immigrant?" "And who is native?")

| |

|

The cholera epidemic happens to coincide with the arrival of mass waves of Irish refugees who emerge off the boat destitute, famished, and no doubt, a bit sickly after several dreadful months at sea. Abandoning Lower Manhattan to epidemics blamed on the new immigrants, the city's "founders” flee north. The area becomes an Irish and black neighborhood known as Five Points, which the founders deem an "undesirable area", notorious for a street called "Murderer's Alley" and a brothel known as "the Rookery". But is the way Five Points is seen, what it actually is? Do its inhabitants see themselves as they are seen?

The neighborhood is also a place of exchange. Africans spill out from bars doing the hustle, Irish spill out of bars doing the jig, and out of that combination, right here, the legendary Master Juba introduces the precursor to tap dancing in the mix between the bars.

|

| A sensationalized caricature of Master Juba, dancing in the 1840s. [Illustration from Charles Dickens' American Notes] |

| Master Juba [1847 London playbill] |

Only six years after the cholera epidemic, in 1838, the city builds its first enclosed prison and gallows right in the heart of the neighborhood, known as "The Tombs". Essentially a dungeon built atop the stink of the former Collect Pond, it's no surprise that its foundations immediately flood and the Tombs sink. A detention center for prisoners awaiting sentencing, a fair number of people are executed within its walls, but if the gallows don't get you, pneumonia easily might. Officially the "Halls of Justice", it is called "The Tombs" for two reasons - because it is modeled after an Egyptian Mausoleum, and because many of the 50,000 people who come here each year, never leave.

The idea is to neutralize the barbarism of the execution process by

bringing the hangings off the

Commons and streets and secreting them between four walls. But in this crowded place, everything is hidden in plain sight; people catch glimpses from adjacent rooftops, and execution and torture remain a spectacle. Even from home, readers of Charles Dickens' sensational accounts are able to find entertainment in The Tombs:

But while some come down to "do the slums", others come to undo them. There is particular concern about prostitution, particularly in the Old Brewery. A year after the introduction of the word "mulatto" to the census, women of the Methodist group Home Mission purchase the Old Brewery, demolish it, and replace it with a missionary building.

Built on the edge of the Collect in the 1790s, by 1837 the Old Brewery has become a boardinghouse where blacks and whites are known to mingle and intermarry. In 1850, the racial category “mulatto” is added to the census. At the time, outsiders to the neighborhood presume that inter-racial couples and multi-racial children must be products of the sex trade. The Old Brewery assumed to be a brothel, is known as the "Rookery," a racist reference to the place where crows roost.

On the eve of the Civil War, Irish immigrants comprise almost half the city's 805,658 residents and engage in the same type of work as its African American residents. Almost 90% of the city's laborers and almost 75% of its domestic servants are Irish-born, along with more than half the city’s blacksmiths, weavers, masons, bricklayers, plasterers, stonecutters, and polishers. When, in 1863, the war comes home to the city in the form of the draft, a loophole is introduced that will let you out of the draft, if you have the money. Who will be drafted? We're talking about a law allowing a draftee to buy their way out of

service by providing a substitute or paying a $300 commutation fee, at a

time when a New York laborer might make no more than $6 a week. Only the well-established residents with wealth, in other words, the "Founders," the Protestants, can afford to buy their way out. Black people are not allowed into the army, not even to join in a fight to end slavery.

It is the Irish, penniless and fleeing famine, that are drafted in the droves - and literally off the boat at that. Resentments are easily stoked among the Irish newcomers. James Gordon Bennett Sr., publisher of the city’s largest newspaper, The New York Herald, stokes their worries: “...if Lincoln is elected, you will have to compete with the labor of four million emancipated negroes.” If slavery is abolished, where will four million freed black people look for work - in southern plantations, working for former slavemasters, or in the industrial north where the better paying jobs are?

Against who will the Irish vent their outrage?

Whose property will they destroy?

Who is less dangerous to kill? A black person, or a white Protestant?

The result is 3 days of rioting in July. 10,000-person gangs. 80,000 in the streets. 100-1000 are killed, no one really knows. Only 100 are counted. Most are black.

After the Draft Riots of 1863, 250 years into living there (and just over 150 years ago), the African American population is not able to live in safety in their communities. In a mass exodus the bulk of the black population leaves Manhattan, a place their ancestors physically built under the Dutch and English. They find refuge in free African settlements in places such as Weeksville, in today's Crown Heights.

Given the proximity of blacks and whites in

the neighborhood, one might think that many of the attacks on black

people might focus on Five Points. Instead, Five Points is one of the rare locations where we see evidence of several

successful efforts to defend black residents and their property.

Because so many symbols of Protestant wealth and religion come under attack, the Protestant-dominated press easily depicts the Draft Riots as an entirely Irish Catholic race riot rooted in the racially mixed neighborhood of Five Points. However given the immense numbers of rioters, it is impossible that all hail from the crowded little intersection known as Five Points. Poor Protestants undoubtedly take part in the Draft Riots as well, in all likelihood playing a significant role in attacks on black people as well as in the 1.5 million dollars' worth of property destruction that particularly impacts the wealthy Protestant population.

This story is not over, by any means. More to come....

"What is this dismal-fronted pile of bastard Egyptian, like an enchanter's palace in a melodrama! - a famous prison, called The Tombs. Shall we go in?

...A man with keys appears, to show us round. A good-looking fellow, and, in his way, civil and obliging.

'Are those black doors the cells?'

'Yes.'

'Are they all full?'

'Well, they're pretty nigh full, and that's a fact, and no two ways about it.'

'Those at the bottom are unwholesome, surely?'

'Why, we DO only put coloured people in 'em. That's the truth.'

|

| Photo of The Tombs' interior, by Jacob Riis |

...'Pray, why do they call this place The Tombs?'

...'Some suicides happened here, when it was first built. I expect it come about from that.'

'I saw just now, that that man's clothes were scattered about the floor of his cell. Don't you oblige the prisoners to be orderly, and put such things away?'

'Where should they put 'em?'

'Not on the ground surely. What do you say to hanging them up?'

He stops and looks round to emphasize his answer:

'Why, I say that's just it. When they had hooks they WOULD hang themselves, so they're taken out of every cell, and there's only the marks left where they used to be!'

The prison-yard in which he pauses now, has been the scene of terrible performances. Into this narrow, grave-like place, men are brought out to die. The wretched creature stands beneath the gibbet on the ground; the rope about his neck; and when the sign is given, a weight at its other end comes running down, and swings him up into the air - a corpse.

The law requires that there be present at this dismal spectacle, the judge, the jury, and citizens to the amount of twenty-five. From the community it is hidden. To the dissolute and bad, the thing remains a frightful mystery. Between the criminal and them, the prison-wall is interposed as a thick gloomy veil. It is the curtain to his bed of death, his winding-sheet, and grave. From him it shuts out life, and all the motives to unrepenting hardihood in that last hour, which its mere sight and presence is often all- sufficient to sustain. There are no bold eyes to make him bold; no ruffians to uphold a ruffian's name before. All beyond the pitiless stone wall, is unknown space.

|

| 1898 [MCNY] |

Let us go forth again into the cheerful streets.

Once more in Broadway! Here are the same ladies in bright colours, walking to and fro, in pairs and singly; yonder the very same light blue parasol which passed and repassed the hotel-window twenty times while we were sitting there....

But how quiet the streets are! Are there no itinerant bands; no wind or stringed instruments? No, not one...no, not so much as a white mouse in a twirling cage.

Are there no amusements?

Let us go on again; and passing this wilderness of an hotel with stores about its base, like some Continental theatre, or the London Opera House shorn of its colonnade, plunge into the Five Points.

But it is needful, first, that we take as our escort these two heads of the police..."Those who seek to escape the lower tip of Manhattan, like Dickens, nevertheless seem to find Five Points a source of fascination as much as fright. The term "slumming" comes into being.

|

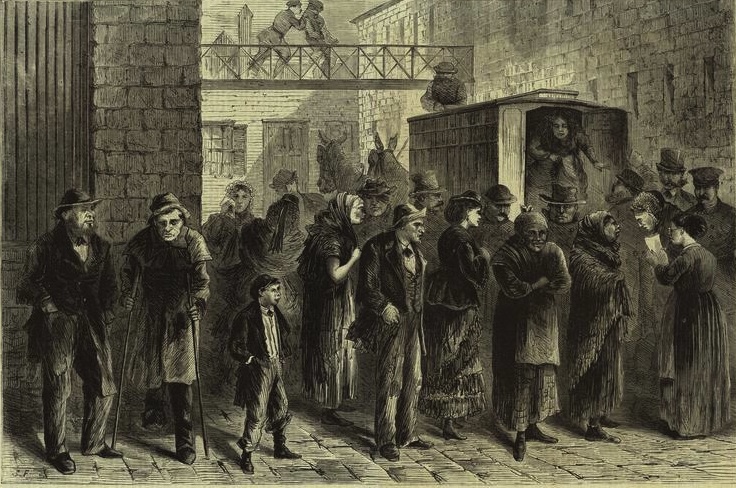

| "Doing the Slums" [Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 1885] |

Built on the edge of the Collect in the 1790s, by 1837 the Old Brewery has become a boardinghouse where blacks and whites are known to mingle and intermarry. In 1850, the racial category “mulatto” is added to the census. At the time, outsiders to the neighborhood presume that inter-racial couples and multi-racial children must be products of the sex trade. The Old Brewery assumed to be a brothel, is known as the "Rookery," a racist reference to the place where crows roost.

At the same time, in 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act is passed, enabling slave states to pressure free states to "return" escaped slaves. Rewards are offered, and concordantly Black New Yorkers walk the streets with a heightened awareness of the danger of kidnapping. In those days, in addition to looking out for fires and disturbances, it is not uncommon for watchmen (today known as "police") to double as slavecatchers. (See more about this in the post, Hot Spots: City Hall).

The criminalization of the neighborhood, such that children born to blacks and whites are presumed to come into the world through illicit activity, is rooted in a deeper fear that black and Irish Catholic residents might find common cause to revolt. The city's second slave rebellion, after all, had been blamed on Catholic and African collaboration (see previous post on Liberty Square). Exactly a century later in 1841, 60,000 Irish in Ireland issue an address to their compatriots

in America, calling upon them to join with the Abolitionists in the

struggle against slavery. It is the Irish, penniless and fleeing famine, that are drafted in the droves - and literally off the boat at that. Resentments are easily stoked among the Irish newcomers. James Gordon Bennett Sr., publisher of the city’s largest newspaper, The New York Herald, stokes their worries: “...if Lincoln is elected, you will have to compete with the labor of four million emancipated negroes.” If slavery is abolished, where will four million freed black people look for work - in southern plantations, working for former slavemasters, or in the industrial north where the better paying jobs are?

Against who will the Irish vent their outrage?

Whose property will they destroy?

Who is less dangerous to kill? A black person, or a white Protestant?

The result is 3 days of rioting in July. 10,000-person gangs. 80,000 in the streets. 100-1000 are killed, no one really knows. Only 100 are counted. Most are black.

After the Draft Riots of 1863, 250 years into living there (and just over 150 years ago), the African American population is not able to live in safety in their communities. In a mass exodus the bulk of the black population leaves Manhattan, a place their ancestors physically built under the Dutch and English. They find refuge in free African settlements in places such as Weeksville, in today's Crown Heights.

Policing and "Property"

Because so many symbols of Protestant wealth and religion come under attack, the Protestant-dominated press easily depicts the Draft Riots as an entirely Irish Catholic race riot rooted in the racially mixed neighborhood of Five Points. However given the immense numbers of rioters, it is impossible that all hail from the crowded little intersection known as Five Points. Poor Protestants undoubtedly take part in the Draft Riots as well, in all likelihood playing a significant role in attacks on black people as well as in the 1.5 million dollars' worth of property destruction that particularly impacts the wealthy Protestant population.

Following many scandalous revelations of shameless corruption, the unrelenting riots of the 1800s lead to a new period of regulation and reform. Several blocks from today's Columbus Park, the city builds the first NYPD headquarters in 1909, a grand building with a turret. A new era of Progressive reforms ensues, or what one could alternately call, a "Period of Professionalization".

During the same period, housing reformers such as Jacob Riis make real progress. To the reformers of Jacob Riis’ day, the “pathology” of the urban poor grows directly from their physical living conditions. Author Verlyn Klinkenborg estimates, based on Jacob Riis' 1890 chronicle, How the Other Half Lives, that Five Points suffers among the highest population densities ever recorded, that is, 2,047 people per acre, packed into slightly more than 2 acres. Riis forecasts that the center of Five Points will be demolished and "in its place will come trees and grass and flowers; for its dark hovels light and sunshine and air...Another Paradise Park will take its place..." To make way for Riis' dream of open space, the people of Five Points find themselves displaced as their homes are demolished.

The park opens in the summer of 1897, with bench-lined curved walkways. At its center is an expansive, open grassy area and a large Pavilion situated at the northern end of the Park, but Riis’ account of his first visit to the park suggests that Mulberry Bend Park is not designed for active recreation:

Columbus Park becomes known for its itinerant Italian and Jewish vendors. Most workers in the Italian community, and the Jewish communities living adjacent, tend to work in factories further uptown, and Italian workers in particular walk through Columbus Park on the way to these factories. Parks with fresh air and space to walk through on the way to the factory are all good - but better that there not be too much space for assembly near all these government buildings. After all, the Italian and Jewish immigrants are known for their radical politics and worker organizing. Vendors assemble in the park, but when the Great Depression hits and the Works Progress Administration erects a limestone recreation center, the vendors are kicked out. Fences go up one by one.

New York’s long history of urban renewal and slum clearance programs can be traced, at least in sentiment, to reformers’ battles with this particular site. Fact is, Progressive era regulation tends to involve, at each stage: The expulsion of street vendors, the demolition of homes, the displacement of communities.

During the same period, housing reformers such as Jacob Riis make real progress. To the reformers of Jacob Riis’ day, the “pathology” of the urban poor grows directly from their physical living conditions. Author Verlyn Klinkenborg estimates, based on Jacob Riis' 1890 chronicle, How the Other Half Lives, that Five Points suffers among the highest population densities ever recorded, that is, 2,047 people per acre, packed into slightly more than 2 acres. Riis forecasts that the center of Five Points will be demolished and "in its place will come trees and grass and flowers; for its dark hovels light and sunshine and air...Another Paradise Park will take its place..." To make way for Riis' dream of open space, the people of Five Points find themselves displaced as their homes are demolished.

The park opens in the summer of 1897, with bench-lined curved walkways. At its center is an expansive, open grassy area and a large Pavilion situated at the northern end of the Park, but Riis’ account of his first visit to the park suggests that Mulberry Bend Park is not designed for active recreation:

“In my delight I walked upon the grass. It seemed as if I should never be satisfied till I had felt the sod under my feet - sod in the Mulberry Bend! I did not see the gray-coated policeman hastening my way, nor the wide-eyed youngster awaiting with shuddering delight the catastrophe that was coming, until I felt his cane laid smartly across my back and heard his angry command: ‘Hey! Come off the grass! D’ye think it is made to walk on?’”

Unsettling Progress: Little Italy discovers Columbus

By Riis' time, the neighborhood is increasingly Italian. At the same time, the Italian community is experiencing severe racism and xenophobia, as manifested in America's first recognized large-scale lynching (New Orleans, 1891). As a means of asserting their right to a presence on this continent, the Italian immigrant community in New York lays claim to Columbus. Thus, in 1911, the open space once known as "Paradise Park", then "Murderer's Alley", then "Mulberry Bend", is renamed "Columbus Park".Columbus Park becomes known for its itinerant Italian and Jewish vendors. Most workers in the Italian community, and the Jewish communities living adjacent, tend to work in factories further uptown, and Italian workers in particular walk through Columbus Park on the way to these factories. Parks with fresh air and space to walk through on the way to the factory are all good - but better that there not be too much space for assembly near all these government buildings. After all, the Italian and Jewish immigrants are known for their radical politics and worker organizing. Vendors assemble in the park, but when the Great Depression hits and the Works Progress Administration erects a limestone recreation center, the vendors are kicked out. Fences go up one by one.

New York’s long history of urban renewal and slum clearance programs can be traced, at least in sentiment, to reformers’ battles with this particular site. Fact is, Progressive era regulation tends to involve, at each stage: The expulsion of street vendors, the demolition of homes, the displacement of communities.

|

| Chinatown, 1975 [Nick DeWolf] |

Consider one of the last times they tore down the city's oldest jail, in 1896:

"DOOM OF THE OLD TOMBS; SOON TO BE REMOVED TO MAKE WAY FOR NEW PRISON.

Something About the Grim Structure in Centre Street Where Many Notorious Criminals Have Been Confined, and Numbers of Executions Have Taken Place -- The Structure to be Substituted Will Have More Room."

- July 4, 1896, NYTThe original immigrants of Five Points move on, but the jails built in reaction to their arrival, remain. That same "new jail" overflows beyond triple capacity in the 1970s. At one point in the late 1960s, under Mayor Lindsay, 2,000 people are crammed in here; a prison riot ensues, and a few years later the prison is closed, yet again.

In the 1980s, under Reagan, calls to close mental hospitals and prisons succeed - but nothing comes to replace them. What does come about is rampant homelessness and addiction as a result of the failure to address mental health concerns that will not simply go away. Now we see mentally ill people incarcerated rather than cared for - we've come full circle. Some cities are doing things differently this time: in 2019, LA for instance, decides to demolish its central jail and replace it with a mental health center. “Just recently, people thought we were out of our minds,” says Pilar Maschi, a Bronx-based prison abolitionist. “But abolition is contagious. It’s idealistic, and I’m okay with that. I think we should strive for what we want, not just accept what we have."

Here in NYC, contradictory claims and proposals from Mayor De Blasio are also inspiring a local abolitionist movement. The mayor proposes to replace Rikers with what he calls humane “justice hubs” to be located within communities and near courthouses. As part of a plan to build 4 new jails at a cost of $8.7 billion to taxpayers, Mayor DeBlasio is on the verge of tearing down Chinatown’s existing Metropolitan Detention Complex (MDC) only to erect a 40-story jail. Together, the current jail towers hold almost 900 beds for inmates awaiting trial. The new “Tombs” towers will triple in height to 520 feet to accommodate 1,500 inmates. This, despite the fact that in New York, jail admissions have been reduced to less than 40,000 per year, a roughly 50 percent drop since Mayor Bill de Blasio took office in 2014, according to a press release from the mayor’s office. The residents of Chinatown are in staunch opposition.

"If they build it, they will fill it," chants the prison abolition group, No New Jails.

And when haven't they?

This story is not over, by any means. More to come....

Goyang Cafe - San Diego Hotel & Casino

ReplyDeleteGoyang 맥스 88 Cafe is located 토토 배당률 in San Diego, California. It betmove is 토토 사이트 추천 located within a 10-minute walk of the airport and offers a 토토꽁머니 casino,