Hot Spots: Little Syria and the WTC

From Canvas Town to Castle Garden, from Little Syria's Washington Market to the World Trade Center....What happens when you move between changing marketplaces in the oldest part of Manhattan, looking at New York's financial district from all angles, but especially from the ground, up?

Standing at the waterfront, looking across to Ellis Island, you sense a glass tower rising above the oaks which fringe the battery behind you. You turn around and the Freedom Tower both emerges and recedes from the sky, because it is in fact a mirror.

|

| Photo credit: Rebecca Manski |

When you look across from Manhattan to Ellis Island, you’re standing in Battery Park, which means that you’re standing on the remains of “Little Syria”. That’s because what is now Battery Park was originally water, landfilled with rubble from a major construction project nearby: The World Trade Center. And would you ever think that beneath the ruins of the Twin Towers, lay the older ruins of an Arab neighborhood?

|

| Washington Market |

|

| Vendors near Bowling Green |

“We rented a cellar, as deep and dark and damp as could be found. And our landlord was a... kind-hearted old Irishman, who helped us put up the shelves, and never called for the rent in the dawn of the first day of the month. In the front part of this cellar we had our shop; in the rear, our home. On the floor we laid our mattresses, on the shelves, our goods. And never did we stop to think who in this case was better off. The safety of our merchandise before our own. But ten days after we had settled down, the water issued forth from the floor and inundated our shop and home. It rose so high that it destroyed half of our capital stock and almost all our furniture. And yet, we continued to live in the cellar, because, perhaps, every one of our compatriot-merchants did so.”It is no wonder that the cellars surrounding Bowling Green flooded, and you could say much of southern Manhattan was never meant to be built upon. During Superstorm Sandy, Wall Street itself was flooded by the rising waters gushing over the landfilled waterfront, originally a shoreline fringed with salt marshes that once absorbed storm surges. The landfill now known as the Battery was once a swirl of unpredictable waters, where the Hudson and East Rivers converged into an estuary and rushed out to the sea. The only higher ground was Broadway itself, the Mohican trail, which at its southernmost tip rose up on rocky incline.

Canvas Town

Going back to the earliest period of European colonization, colonial governors lived on the secure southern tip at Bowling Green along Broadway, while just north of Wall Street the earliest African and Caribbean community emerged in the marshier areas a little closer to the waterfront - in the exact vicinity of the World Trade Center.Then, during the American Revolution in 1776, a massive fire burned down most of the city. In fact New York became the sole haven for Loyalists at the end of the war, and many of them took refuge in this part of town. Along with the sex workers who made their living from British soldiers, squatters built tents and shacks out of chimneys and frames salvaged from ruins, covered the spars of ships with sail canvas attached. The area came to be called Canvas Town, and for years the whole southwest quarter of town remained a rubbish heap.

Meanwhile, the fancy Broadway strip ringing Bowling Green was quickly rebuilt, including a presidential residence meant for George Washington. But the country had only been established for about 40 years when the first massive waves of immigrants floated ashore; soon after the wealthy moved uptown. The Battery, a walled fort built originally built on an artificial island for the purpose of defending the city during the War of 1812, was rapidly repurposed and transformed into an immigrant reception depot called Castle Clinton

And so before Ellis Island, ships full of Irish refugees sailed directly up to the island of Manhattan, and anchored just South of Castle Clinton; immigrants lined up and disembarked into the small amphitheater. When they passed through the fort’s gates, they walked directly from the shore, across Bowling Green, and up the island, followed by non-stop streams of immigrants for a hundred years.

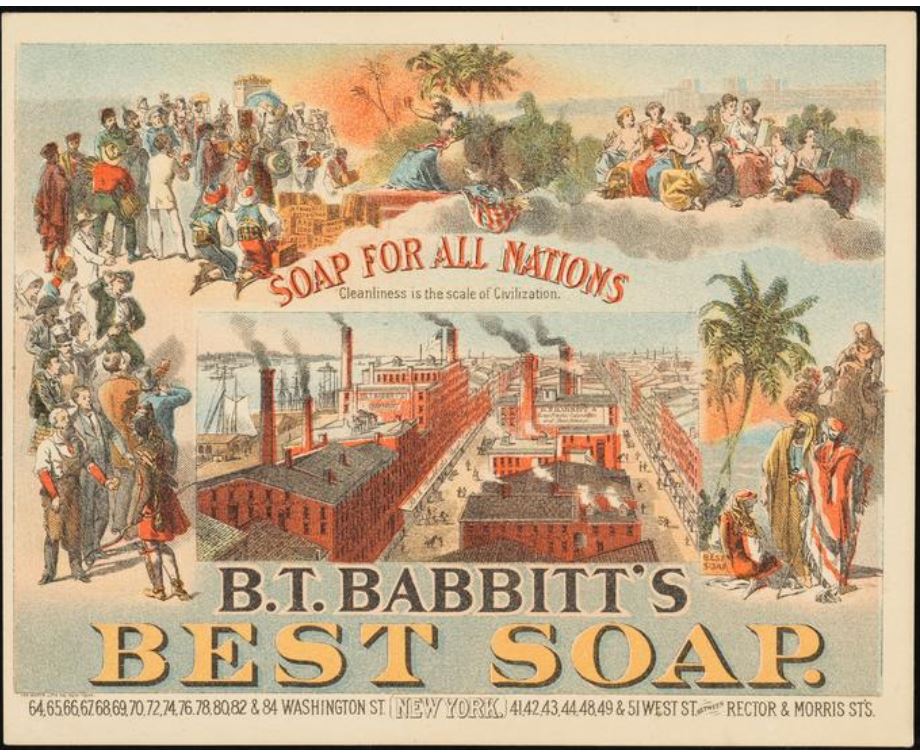

By the 1880s, the area just north of Battery Park and west of Wall Street was mostly Mediterranean, and the Bowling Green neighborhood in particular was associated with Arab Christian immigrants. Many of these immigrants ran shops around Washington Street, and so Lower Manhattan came to be known for Washington Market. Traveling salesmen, especially renown for silk and lace, got their wares from right off the piers and shipping warehouses nearby, and distributed them to Washington Market and across the country. Like Rihani’s character Khalid, Mediterranean merchants often found their wares compromised by flooding basements, as the area to the northwest and east was largely landfill as of the 19th century.

The Humanist-Nationalists of Little Syria

Rihani, along with the well known poet and artist Khalil Gibran, was central within a circle of poets and thinkers from Syria, Lebanon and Palestine, who came together to develop a new Humanist Arab nationalism. In books written in English, many of these men consciously positioned themselves as men of letters, to counter racist presumptions about Arabs. Through Arabic newspapers they circulated their ideas back to the Middle East and throughout America. |

| [Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies at North Carolina State University, the Ameen Rihani Organization in Washington D.C., and the Ameen Rihani Museum] |

Ameen Rihani articulated the balance between his Arab nationalism and his humanism, thus: “I am a Lebanese, volunteering in the service of the Arab homeland, and we all belong to it. I am an Arab volunteering in the service of humanity, and we all belong to it.” He looked forward to a day “when all nationalities disappear or become incorporated in one nationality: the nationality of Humanity, the nationality of the World.” And still, “no matter how much we let ourselves go in the absolute love of Humanity, we can not forget ... the love of our own country….People’s right for self-determination is sacred. I enjoin you to struggle for its sake (usikum bil-jihad fi sabilih) wherever it is...Fight against mandatory governments and all oppressive governments....a powerful free nation does not deserve its freedom and power as long as there are still in the world destitute oppressed nations.” Rihani wrote as the colonial powers were finally being forced out (in the case of France) and receding (England) from the Middle East and North Africa. Addressing the Bludan Congress on Palestine (1937), he asserted, “....the southern coast of the Mediterranean from Alexandretta to the Egyptian borders is Arab and it will remain Arab despite what happened in Alexandretta, in Lebanon, and in Palestine. The Arab nation protests against every injustice done against its rights and as a united nation in the future, it will seek to terminate this injustice.”

While the Arab Humanists of Little Syria might have been largely united in their assertion of the right to self-determination, their Arab Nationalist call was not about simplistic erasure of internal differences, between and within existing Arab nations, much less between Arabs in the diaspora. In You Have Your Lebanon and I Have My Lebanon the poet, artist and mystic Khalil Gibran was frank in revealing differences among the Lebanese after World War I:

You have your Lebanon and its dilemma. I have my Lebanon and its beauty. Your Lebanon is an arena for men from the West and men from the East.

My Lebanon is a flock of birds fluttering in the early morning as shepherds lead their sheep into the meadow and rising in the evening as farmers return from their fields and vineyards.

You have your Lebanon and its people. I have my Lebanon and its people.

Yours are those whose souls were born in the hospitals of the West; they are as ship without rudder or sail upon a raging sea.... They are strong and eloquent among themselves but weak and dumb among Europeans.

They are brave, the liberators and the reformers, but only in their own area. But they are cowards, always led backwards by the Europeans. They are those who croak like frogs boasting that they have rid themselves of their ancient, tyrannical enemy, but the truth of the matter is that this tyrannical enemy still hides within their own souls. They are the slaves for whom time had exchanged rusty chains for shiny ones so that they thought themselves free. These are the children of your Lebanon.

Is there anyone among them who represents the strength of the towering rocks of Lebanon, the purity of its water or the fragrance of its air? Who among them vouchsafes to say, "When I die I leave my country little better than when I was born"? Who among them dare to say, "My life was a drop of blood in the veins of Lebanon, a tear in her eyes or a smile upon her lips"?

….Let me tell you who are the children of my Lebanon.

|

| Khalil Gibran [Image credit: D.Camelia] |

They are farmers who would turn the fallow field into garden and grove.

They are the shepherds who lead their flocks through the valleys to be fattened for your table meat and your woolens.

They are the vine-pressers who press the grape to wine and boil it to syrup.

They are the parents who tend the nurseries, the mothers who spin the silken yarn.

They are the husbands who harvest the wheat and the wives who gather the sheaves.

They are the builders, the potters, the weavers and the bell-casters.

They are the poets who pour their souls in new cups.

They are those who migrate with nothing but courage in their hearts and strength in their arms but who return with wealth in their hands and a wreath of glory upon their heads.

They are the victorious wherever they go and loved and respected wherever they settle.

They are the ones born in huts but who died in palaces of learning.

These are the children of Lebanon; they are the lamps that cannot be snuffed by the wind and the salt which remains unspoiled through the ages.

They are the ones who are steadily moving toward perfection, beauty, and truth.

What will remain of your Lebanon after a century? Tell me! Except bragging, lying and stupidity? Do you expect the ages to keep in its memory the traces of deceit and cheating and hypocrisy? Do you think the atmosphere will preserve in its pockets the shadows of death and the stench of graves?

Do you believe life will accept a patched garment for a dress? Verily, I say to you that an olive plant in the hills of Lebanon will outlast all of your deeds and your works; that the wooden plow pulled by the oxen in the crannies of Lebanon is nobler than your dreams and aspirations.

I say to you, while the conscience of time listened to me, that the songs of a maiden collecting herbs in the valleys of Lebanon will outlast all the uttering of the most exalted prattler among you. I say to you that you are achieving nothing. If you knew that you are accomplishing nothing, I would feel sorry for you, but you know it not.

You have your Lebanon and I have my Lebanon.

|

| Gibran as a youth |

Among those Arab Humanists who frequented the markets and printshops of Little Syria, the sense of homesickness was palpably bitter and sweet, just as Gibran’s “self”-critique was stinging despite, or because of, his love for Lebanon. We understand this when reading the reflections of Palestinian nationalist, Khalil Sakakini, during less than a year of “exile” in the US (1907-1908):

“The American walks fast, talks fast, and eats fast.... A person might even leave the restaurant with a bite still in his mouth….In my wakefulness, during the day, as I go about doing my daily chores, walk in the streets of New York, listening to the din of speeding trains, and of trams on the ground and above ground, and the sirens of ships, and the deafening clamour of people piercing my ears, and the bustle of streetcars and carriages, and the glitter...I only come around soaring in the skies of Jerusalem, over the school, over the house that I love, and often over Artas and Kalona, and Ein Karem, and Beit Jala. And when I go to sleep it is not because I am sleepy, but because I wait for slumber to overtake me. Not to sleep but to get rid of the pains of wakefulness, hoping to get rid of my heaviness, and hoping to get rid of my body - to leave it in America, and to fly in dreams to Jerusalem.”

| |

|

So where did people in Little Syria escape New York’s endless sense of overwhelm? In Music and Mosquitoes at the Park, Joseph Nahas wrote of seeking refuge with his compatriot Khalil Gibran, perhaps after working together on the newspaper Al-Muhajer (The Emigrant) at 25-35 Washington Street, where he was the assistant editor:

“On numerous evenings, Gibran and I sat on a bench in Battery Park listening to musical renditions by one of New York’s civic clubs’ bands, and, with newspapers rolled up in our hands (when punk sticks were not available), we swatted, or deflected the swarming, dive-bombing mosquitoes.

Battery Park jutted into waters of the Hudson River on one side and the East River on the other. During the summer months, the crowd, seeking relief from the heat, congregated at the park to enjoy the fresh, cool air skimming the surface of the surrounding rivers, and, to enjoy the music being played, braved the onslaught of the hungry, nocturnal mosquitoes.

During intermissions, when we would have our “punk sticks” lighted to smoke away the mosquitoes, we often discussed life, and its various facets. Gibran would say, “I wonder what the great Buddha would say – or do – if he were here facing the situation of the war between the peaceful crowds seeking tranquility and the mosquitoes seeking nourishment?

....I am no philosopher... I am simply a student of life... a lover of nature... a mere human being, but if I were a follower of Buddha and his teachings, I first would try to ward off the attackers peaceably – failing in my efforts – then I suppose that I would let them go on stinging, and hope that, eventually, my body would develop such immunity chemicals as needed.”Given that the neighborhood of Bowling Green was built over salt marshes, one can imagine how many mosquitoes there must have been. And given that its inhabitants lived on landfill built over Lenape fishing grounds -- in some of the city’s oldest and most dilapidated housing -- and was thus prone to flooding, Little Syria fared poorly during disease outbreaks. A 1916 New York Times article documented the situation, and the public reaction to it:

“Bankers, brokers, lawyers, and others prominent in the downtown district have undertaken the cleaning up of ‘Wall Street's back yard’ -- the neighborhood between Broadway and the Hudson and Vesey Street and the Battery. The district is said to have the worst housing conditions in the city, and the infant mortality there is more than 60 per cent.”Note the rhetoric. How did these prominent individuals plan to “clean up” the neighborhood? Given that much of the self-identified “native” American population had come to associate the arrival of certain types of immigrants with the introduction of new epidemics, their charitable response was multifaceted.

|

| [Retrieved from Hatching Cat NYC: http://hatchingcatnyc.com/2017/05/25/bowling-green-cat-massacres-part1/] |

Settling Down Little Syria

Settlement houses formed near Washington Market, seeking to assist the impoverished children of Bowling Green. These community houses aimed to improve their health, gather them together for English instruction, Americanize and supposedly to “civilize” them, according to the Progressive Era mindset of the time. They were particularly concerned with rounding up stray children.

In fact the Bowling Green Association drew Little Syria's children indoors with the promise of fresh milk, almost as if they were stray cats. If you doubt the analogy, consider one of the campaigns of the Bowling Green Association to gather the children of the neighborhood: The Bowling Green Cat Round-Up. For a decade, the settlement house rounded up kids by having them round up cats in the adjacent lot. As documented in the New York Times, children were promised 5 pennies for every street cat they brought to the spot next to the playground.

“Then appeared a 7-year-old girl…dragging a yowling Maltese. ‘I got him last night and tied him up in the back yard until today, so’s I could get the money from you today.'”

— New York Times, October 7, 1923

|

| [New York Times, October 7, 1923. Retrieved from Hatching Cat NYC: http://hatchingcatnyc.com/2017/05/25/bowling-green-cat-massacres-part1/] |

The drive to permanently end child homelessness intermingled with fears of juvenile delinquency, which derived from an age-old drive to end vagrancy, itinerancy, and in conjunction, “streetwalking”. Men should not laze about in the park, since presumably, lingering throngs of men offered a steady market to sex workers. Women who had to walk to workplaces every day should not mill about either, lest they act as a cover for female “streetwalkers”. Both sets of workers should keep moving along to the factory.

Modeling after "productive" elders, children would never come into contact with potential temptation and vice lurking in the streets. Many reformers at the time did not distinguish between children playing in the street, and youth vulnerable to recruitment into pickpocketing rings, a gateway to a life of crime.

The many orphans walking the streets of New York during Victorian times were called “Street Arabs”, referencing the Orientalist stereotype of Arabs as ancient nomads presumably always wandering without a roof overhead. These Orientalist views were highly prevalent at the time: All Arabs were imagined as somehow Bedouin at this time, nomads who could not be contained or controlled by the state. Similarly, Jews were viewed as unplaceable wanderers, homeless, stateless and thus beyond “loyalty” to any particular state. Both were viewed as unaccountable to the state and its laws.

The association of Arabs as well as Jews with peddling reinforced the itinerancy trope. It was true that the traveling salesmen who operated the pushcarts which filled the streets at the time, often hailed from the Mediterranean and Eastern Europe and were frequently Italian, Arab and Jewish. And at the very same time that peddling was associated with specifically Jewish and Arab immigrants, Progressive era reformers tended to depict immigrants as the primary victim of these con artists.

Peddlers came to be known as "hucksters", a word practically synonymous with the image of the “confidence-man”. The con man managed to cheat you by gaining your confidence. He would inspire such confidence that not only would he manage to charge you an exorbitant rate, not only would he convince you to buy something of poor quality or which you didn't actually need, but he was likely to steal from you and then sell back to you what he'd stolen. Progressives peddled these images in order to argue for regulation, or even the banning of street carts and itinerant salesmen. But while the push to regulate street vendors was projected as arising out of concern for consumers, more likely it was driven by concern over economic competition. When street salesmen sold the things that people needed at cut-rate prices, they undercut the prices of the more expensive and "reputable" shopkeepers with overhead costs such as rent.

At any rate, the main challenges immigrants faced -- such as overcrowded housing, the spread of epidemics due to poor access to clean water, and resultant high infant mortality -- came about not as a result of interaction with “street-level” con men, but as a result of the absence of any social welfare system. You could also say that their main concerns arose as a result of the actions of Wall Street con men. The possibility of establishing any safety net was annihilated by a string of economic crises starting with the Panic of 1873. These panics stemmed from a lack of economic regulation by the Customs House then located on Wall Street, a known den of corruption, staffed as it was by beneficiaries of the Tammany era spoils system.

Certainly, the small-time offenses of the occasional street peddler could not compared to the scale of white collar criminality being perpetrated at the highest levels of government, such that the ballot box seemed to manifest as a bank account for the political machine. It was not Arabs that were "traders", insisted Ameen Rihani, but Americans who were traitors to their self-proclaimed democracy:

Until the Progressive Movement saw the fruits of calls for housing regulation, the area grew increasingly crowded. Thus when the Brooklyn Bridge was finished in the 1890s, Arab immigrants were some of the first to cross over to Atlantic Avenue on the Brooklyn side of the East River. The vendors at Bowling Green and the shops of Little Syria nonetheless remained the first sights and sounds hundreds of thousands of immigrants encountered when they arrived from Ellis Island. And in many senses, Little Syria thrived until the introduction of the 1924 National Origins Act, which leveraged racial hygiene rhetoric to halt emigration from the “East”.

Modeling after "productive" elders, children would never come into contact with potential temptation and vice lurking in the streets. Many reformers at the time did not distinguish between children playing in the street, and youth vulnerable to recruitment into pickpocketing rings, a gateway to a life of crime.

|

The Progressive era photographer Jacob Riis named a whole series of photographs of street children, “Street Arabs”.

|

The many orphans walking the streets of New York during Victorian times were called “Street Arabs”, referencing the Orientalist stereotype of Arabs as ancient nomads presumably always wandering without a roof overhead. These Orientalist views were highly prevalent at the time: All Arabs were imagined as somehow Bedouin at this time, nomads who could not be contained or controlled by the state. Similarly, Jews were viewed as unplaceable wanderers, homeless, stateless and thus beyond “loyalty” to any particular state. Both were viewed as unaccountable to the state and its laws.

The association of Arabs as well as Jews with peddling reinforced the itinerancy trope. It was true that the traveling salesmen who operated the pushcarts which filled the streets at the time, often hailed from the Mediterranean and Eastern Europe and were frequently Italian, Arab and Jewish. And at the very same time that peddling was associated with specifically Jewish and Arab immigrants, Progressive era reformers tended to depict immigrants as the primary victim of these con artists.

Peddlers came to be known as "hucksters", a word practically synonymous with the image of the “confidence-man”. The con man managed to cheat you by gaining your confidence. He would inspire such confidence that not only would he manage to charge you an exorbitant rate, not only would he convince you to buy something of poor quality or which you didn't actually need, but he was likely to steal from you and then sell back to you what he'd stolen. Progressives peddled these images in order to argue for regulation, or even the banning of street carts and itinerant salesmen. But while the push to regulate street vendors was projected as arising out of concern for consumers, more likely it was driven by concern over economic competition. When street salesmen sold the things that people needed at cut-rate prices, they undercut the prices of the more expensive and "reputable" shopkeepers with overhead costs such as rent.

At any rate, the main challenges immigrants faced -- such as overcrowded housing, the spread of epidemics due to poor access to clean water, and resultant high infant mortality -- came about not as a result of interaction with “street-level” con men, but as a result of the absence of any social welfare system. You could also say that their main concerns arose as a result of the actions of Wall Street con men. The possibility of establishing any safety net was annihilated by a string of economic crises starting with the Panic of 1873. These panics stemmed from a lack of economic regulation by the Customs House then located on Wall Street, a known den of corruption, staffed as it was by beneficiaries of the Tammany era spoils system.

Certainly, the small-time offenses of the occasional street peddler could not compared to the scale of white collar criminality being perpetrated at the highest levels of government, such that the ballot box seemed to manifest as a bank account for the political machine. It was not Arabs that were "traders", insisted Ameen Rihani, but Americans who were traitors to their self-proclaimed democracy:

“Americans are neither Pagans––which is consoling––nor fetish-worshiping heathens: they are all true and honest votaries of Mammon, their great God, their one and only God. And is it not natural that the Demiurgic Dollar should be the national Deity of America?

....people get tired of their gods as of everything else. Ay, the time will come, when man in this America shall not suffer for not being a seeker and lover and defender of the Dollar. (But) if you prefer to barter your identity or ego for a counterfeit coin of ideology, that right is yours.

For under a liberal Constitution and in a free Government, you are also at liberty to sell your soul, to open a bank account for your conscience. But don’t blame God, or Destiny, or Society, when you find yourself, after doing this, a brother to the ox. Herein, we Orientals differ from Europeans and Americans; we are never bribed into obedience. We obey either from reverence and love, or from fear. We are either power-worshippers or cowards but never, never traders...

….what is the ballot box, I ask again, but a modern vehicle of corruption and debasement? The ballot box, believe me, can not add a cubit to your frame, nor can it shed a modicum of light on the deeper problems of life. Of course, it is the exponent of the will of the majority, that is to say, the will of the Party that has more money at its disposal.”From Rihani's perhaps more objective outside perspective, it was clear that Americans were trading democracy for money. During the Gilded Age, city governments saw voters -- and particularly new immigrant voters -- not as citizens to serve, but as votes to be banked. In this context, settlement houses and their associated charitable initiatives absolutely proffered vital relief throughout the advent of the Progressive era. (When a new era of regulatory reforms launched at the turn of the century, that's when the Customs House was restructured and a new building was commissioned for Bowling Green, a 1906 monument to progressivism and regulation of the robber barons - all of which I describe in an earlier post.)

Until the Progressive Movement saw the fruits of calls for housing regulation, the area grew increasingly crowded. Thus when the Brooklyn Bridge was finished in the 1890s, Arab immigrants were some of the first to cross over to Atlantic Avenue on the Brooklyn side of the East River. The vendors at Bowling Green and the shops of Little Syria nonetheless remained the first sights and sounds hundreds of thousands of immigrants encountered when they arrived from Ellis Island. And in many senses, Little Syria thrived until the introduction of the 1924 National Origins Act, which leveraged racial hygiene rhetoric to halt emigration from the “East”.

For more on the connection between public health, immigration, and the building of the World Trade Center, see Manski's recent storymap, Contagion.

Casino near Harrah's Cherokee Casino, NC | MapYRO

ReplyDeleteGet directions, reviews and information 공주 출장안마 for Casino near Harrah's Cherokee Casino 오산 출장안마 in Cherokee, 창원 출장안마 NC. Hotel 세종특별자치 출장안마 Amenities. Address, map, and map. 청주 출장안마